Marketers chase metrics while missing what actually drives human behavior. They've mastered the science of tracking what people do but remain blind to the cultural contexts that explain why they do it.

Anthropology offers the missing framework revealing the invisible patterns, rituals, and symbolic meanings that shape consumer decisions long before they click "buy."

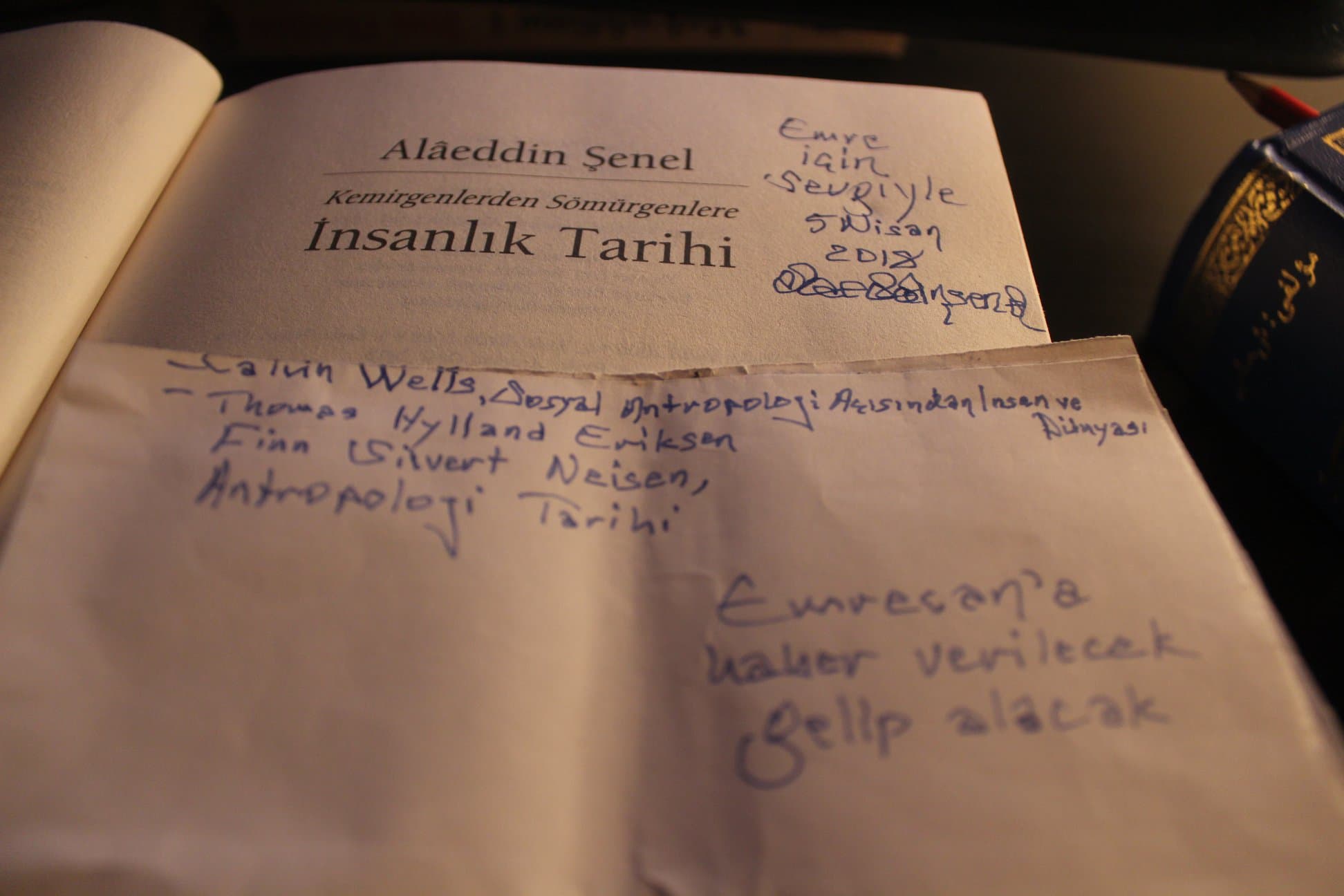

Great minds in business read the market like anthropologists:

- Learns at a distance, observing without imposing their own biases

- Understands the invisible forces shaping consumer decisions

- Develops authentic strategies rather than imitating competitors

- Sees products as vehicles for meaning, not just solutions to problems

Why every marketer should learn anthropology

Anthropology studies humans as cultural beings shaped by invisible social forces. It reveals the hidden patterns directing human behavior across societies. While most businesses focus on immediate consumer actions, anthropologists see the deeper cultural systems driving these behaviors.

The gap between cultural narratives and lived realities is where market opportunities hide. Anthropologists are trained to identify these disconnects. They recognize unspoken social contracts, interpret symbolic exchanges, and understand how communities create meaning together.

When Netflix expanded to India with its American content strategy, it flatlined against local competitors who understood the cultural significance of family viewing and regional storytelling traditions. When Walmart failed in Germany, it wasn't because Germans didn't want low prices, it was because they rejected the forced friendliness of greeters and the cultural assumptions embedded in store layouts.

A marketer with anthropological insight doesn't merely track what people buy, they grasp why certain choices feel inevitable to consumers. They recognize how identity, belonging, and cultural values shape market decisions. This perspective transforms marketing from reactive tactics into cultural navigation.

Observation with a distance

I've watched brilliant marketers fail spectacularly because they couldn't separate their own cultural assumptions from universal truths. They projected their values onto customers and then wondered why their "perfect" solutions gained no traction.

The most valuable skill anthropology teaches is distance, it's the ability to remove yourself from your biases and see situations as they truly are. This skill alone can transform your marketing approach.

When you create distance, you start seeing connections invisible to those embedded in the system. You notice patterns in customer behavior that competitors miss. You recognize market shifts before they become obvious.

Anthropologists develop a capacity to observe without judgment, to understand without imposing their values. This perspective lets you read markets with unusual clarity. You spot emerging opportunities others can't yet see.

When you step back and truly observe without judgment, patterns emerge that were invisible before.It strengthens your market reading abilities.

When Apple created the iPod, they succeeded not because they built better technology (they didn't), but because Jobs maintained anthropological distance from the existing music industry. He saw that people's relationship with music wasn't primarily technological but cultural, about identity, curation, and personal expression. This cultural insight, not technical superiority, created a category-defining product.

"Thick Description" methodoloy

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz introduced the concept of "thick description", going beyond surface observations to capture the full context and meaning of behaviors. This approach is transformative for marketing.

Thin description tells you what customers are doing. Thick description reveals why they're doing it. It captures the cultural context, social meanings, and underlying motivations driving behavior.

Consider a simple act like buying coffee. Thin description tracks transactions. Thick description reveals the ritual significance, identity signaling, and community aspects of the purchase. This deeper understanding enables more resonant marketing.

Consider Coca-Cola's "Share a Coke" campaign. The data-driven approach would see it as a personalization tactic that increased engagement. The thick description reveals how it brilliantly leveraged specific cultural values around individual recognition, gift-giving rituals, and social connection. This deeper understanding explains why the campaign succeeded in individualistic Western markets but required significant adaptation in collective Eastern cultures.

Or examine Peloton's catastrophic 2019 holiday ad. The thin description showed a husband giving his wife an exercise bike. The thick description,which the company completely missed, revealed how the ad unintentionally tapped into troubling cultural narratives around body image, gender roles, and class privilege. This cultural blindness cost them $1.5 billion in market value.

Without thick description, you're navigating markets blindfolded, occasionally succeeding through luck but inevitably stumbling into cultural landmines you never saw coming.

Imagined communities and their business applications

Humans naturally form what anthropologists call "imagined communities", groups united by shared narratives rather than direct relationships. These communities are built around collective histories and shared values.

Successful brands don't just sell products, they create imagined communities. Apple users, Harley Davidson riders, and CrossFit members are communities with shared identities and stories as well.

These communities develop through carefully cultivated narratives and rituals. They create belonging that transcends the practical value of products. This belonging drives loyalty no feature set can match.

The same principles apply within companies. Organizational culture is effectively an imagined community. Companies with strong cultures build shared memories, rituals, and values that unite employees beyond transactional relationships.

CrossFit didn't become a global phenomenon by offering better exercise, it succeeded by creating a community with its own origin myths, heroes, rituals, and identity markers. The workout is merely the price of admission to the community, not the product itself.

Rituals' power in consumer behavior

Rituals transform ordinary actions into meaningful experiences. They create order and meaning in chaos. Smart marketers don't just sell products, they design rituals around them.

Consider unboxing videos. They've become modern consumption rituals, turning the mundane act of opening a package into a shared experience filled with anticipation and delight. The best product experiences are designed with ritual elements in mind.

Rituals create habitual behavior that strengthens brand loyalty. The morning coffee ritual, the skincare routine, the workout sequence, these aren't just habits but meaning-making activities.

Companies that understand the ritual dimension of consumption design experiences that resonate at a deeper level. They transform ordinary products into vehicles for meaning.

Apple meticulously crafts rituals. The unboxing experience, the startup sequence, even the store layout creates a series of microrituals that transform a mundane purchase into a meaningful experience. These aren't accidental, they're deliberately engineered to create cultural significance.

Starbucks succeeded by ritualizing coffee consumption, creating a "third place" with its own language, customs, and social norms. The ritual ordering process isn't inefficient by accident; it's deliberately designed to make customers feel like insiders who have mastered a cultural code.

Pierre Bourdieu's concepts of habitus and capital

Bourdieu's concept of habitus, internalized dispositions that guide our preferences, explains why different consumer groups make dramatically different choices despite similar income levels.

Cultural capital, knowledge, tastes, and behaviors valued within specific groups, influences consumer decisions far more than most marketers realize. People buy products that align with their self-perception and the cultural capital they aspire to possess.

This explains why status signaling varies dramatically between communities. Wall Street bankers and Silicon Valley engineers signal status in completely different ways, despite similar income levels. Understanding these differences enables precise brand positioning.

When someone pays $50,000 for a luxury watch that tells time less accurately than a $10 digital watch, they're not making an irrational decision. They're purchasing cultural capital that functions as currency in specific social circles. Understanding this isn't just interesting, it's essential to creating products and marketing that resonate with specific communities.

Effective marketing understands what forms of cultural capital matter to specific audiences and positions products as vehicles for acquiring that capital. This requires understanding the often unspoken status hierarchies that exist within different communities and how products function as markers within those hierarchies.

Raymond Williams on authentic modernization

Cultural theorist Raymond Williams observed that becoming truly modern requires developing your own history and canon. Countries that merely copy "modern" nations create modernization, not authentic modernity.

This insight applies directly to business. Companies that copy industry leaders create pale imitations, not innovative enterprises. True market leadership comes from developing your own authentic identity and approach.

Each company must find its unique pathway to growth. Copying others' strategies creates, at best, temporary advantages. Sustainable success requires developing approaches authentic to your specific situation and capabilities.

When Chinese companies tried to replicate Silicon Valley's innovation culture through open office plans and casual dress codes, they created superficial copies that failed to produce innovation because they conflicted with deeper Chinese cultural values around hierarchy and formality. They achieved modernization without modernity.

The same pattern plays out constantly in business. Companies adopt "best practices" without understanding that these practices emerged from specific cultural contexts that may not exist in their organizations. They implement Agile methodologies without the cultural foundations of trust and autonomy that make Agile effective. They copy Apple's minimalist design language without Apple's cultural commitment to simplicity.

The tension between global and local

The most sophisticated brands balance global reach with local relevance, what anthropologists call "glocalization." They maintain core brand identity while adapting to local cultural contexts.

This balance requires deep anthropological understanding. What elements of your brand are universal? What elements require cultural translation? These questions determine success in new markets.

Cultural sensitivity isn't just ethical, it's profitable. Brands that respect local customs while offering global benefits create deeper connections than those imposing standardized approaches.

McDonald's didn't succeed globally by forcing American fast food on other cultures. It succeeded by maintaining core brand elements while adapting to local cultural systems, creating the McAloo Tikki burger in India, the Teriyaki McBurger in Japan, and the McKroket in the Netherlands. These weren't just menu adaptations but recognitions of the cultural significance of food in different societies.

Truly Indian Burger

The companies that fail internationally almost always make the same mistake: they confuse their cultural assumptions with universal truths. They assume that values like convenience, efficiency, or even beauty are defined the same way across cultures, only to discover that these concepts have radically different meanings in different cultural contexts.

Successfully navigating this tension requires not just tactical flexibility but a fundamental humility about the universality of your cultural assumptions. It requires understanding when standardization creates meaningful efficiency and when it creates cultural friction that undermines your value proposition.

Marshall Sahlins and contextual needs

Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins challenged assumptions about Stone Age poverty in his groundbreaking work. He argued that hunter-gatherers weren't deprived, they simply had different needs and contexts.

This insight applies directly to business strategy. What's essential for one company may be irrelevant for another. The tools, processes, and strategies that drive success vary dramatically based on context.

The fallacy of establishing "must-haves" based on other companies leads to wasted resources and misaligned priorities. Each organization must evaluate needs within its specific context rather than adopting industry standards without questioning.

When startups blindly adopt the organizational structures of tech giants like Google or Facebook, they're committing the same fallacy Sahlins identified, assuming that lacking Google's structures means they're somehow "primitive" or "underdeveloped" rather than recognizing that their context demands different approaches.

Success comes not from following others but from developing approaches suited to your unique situation. The anthropological perspective forces this contextual thinking rather than blind imitation.

Anthropological marketing is a fundamental reconceptualization of what business is and how it creates value. It recognizes that all economic activity is embedded in cultural systems and that understanding these systems is not optional but essential to creating meaningful and sustainable value.

Netflix lost billions trying to apply American content strategies globally. Microsoft wasted years pushing products that violated cultural expectations about privacy and control. Countless startups have failed not because their technology didn't work but because they fundamentally misunderstood the cultural contexts they were entering.